In recent months, debate has grown around how we question children in schools, whether questioning can trigger anxiety, and whether teachers should avoid it altogether. As a freelancer working across education and youth work, I wanted to explore what this means in practice, because questioning is at the very heart of how young people learn.

So that question you can’t answer…

That does leave me with a bit of a predicament: I’ll keep talking to the wall and hopefully you’ll still be listening by the end.

Seems weird right? But this is potentially the way things could go if those news headlines are correct. Teachers may be asked (ironically) to not pose questions to their classes due to the emotional turmoil and strain it can put on young people.

How does this impact the work that educators are there to do? More specifically, what impact does it have for organisations like Justice in Motion who have a small window of opportunity to build a relationship in order to deliver an educational programme?

Concept Crafting for the Classroom

Over the past two years I’ve worked as the Education Manager with Justice in Motion, delivering impactful content in schools up and down the country around county lines, knife crime, and child exploitation to young people in Years 5 through Year 10.

When I was asked to design the programme, having an education and youth work background, I didn’t so much as begin with a blank page but approached it with the firm intention that engagement was central to what we were offering. Schools and youth work settings are built on educational systems – the former is more prescribed but the latter still has frameworks to follow.

Both the Delors Report (UNESCO, 1996), which is widely reference in UK education policy, and the core values of youth work (NYA-JNC endorsed), line up with each other to have something of a shared focus in four key areas which can be summarised as below:-

- Learning through experience and reflection

- Skills for life and action

- Personal growth and self-actualisation

- Community, diversity, and mutual respect

Dive deeper and words such as social cohesion, inclusion, and participation can be found. These combined became the basis of the work we were to deliver.

The entire programme is built on the foundation that the work will engage with young people on a level that they can participate fully in, give space for reflection while simultaneously building on any prior knowledge, as well as offering creative skills-based activities that may inspire them to take an exciting new, and possibly completely different path than they were expecting.

The main programme was to have three clear strands.

- A presentation that could be delivered at the start of the day as a standalone or on a rolling basis to various groups across the day. Essentially hitting the masses with information.

- Workshops which would blend creativity with topic education, building on the presentation.

- A six session work pack that schools who had booked us could use in lesson time, delivering before, during, and after our visit as they saw fit.

On point three it would be challenging enough until a throwaway comment of ‘Wouldn’t it be great if it all linked to the PSHE/RSHE touchpoints?’ was raised. ‘Even more so if the sessions linked to every lesson type in the curriculum (ie.: English, Maths, Science, Art, even DT!).

I’m a visual worker, and in designing any workshops or programmes, I’ve always found ‘brain dumping’ ideas as quickly as possible to have its benefits, be this on paper, laptop, or a whiteboard. Often, utilise a blended approach of all three. My initial document was heavily detailed. Pages long with many columns where cross-referencing occurred, I not only used activity ideas I’d run in previous youth settings, but drew on my days in youth theatre and Scouting and the fun activities we did there.

I plotted these against lesson expectations I found online, and to add further detail, dove into Ofsted’s inspection framework to try and draw out any key links I could. It’s all well and good delivering to a school, but at the end of the day, they have to be able to evidence its benefits. It’s also quite amazing how once your creative juices are flowing, even if you draw on rigid frameworks, you can produce some really imaginative ideas.

The question was how I was to fit everything into a six-session programme that could be delivered by teachers in schools on limited resources, minimal prep time, and a presumption of no knowledge began. A caveat that I’m not saying schools don’t know about county lines, but I had to approach this in the old school way of ‘Imagine you’re having to explain this to an alien’ because even as adults we have differing knowledge levels, and in the heat of the moment, if you have to drop everything and deliver something new, it needs to be accessible and for you as the teacher to feel as though you can stand at the front with confidence.

So here we are. Reams of pages with columns that seem to stretch on for ever, linking to lessons and frameworks, notes scrawled across it, a rough outline of a presentation, and a fast-approaching deadline, but getting from that to delivery is no mean feat.

Creative Curriculum Considerations

I’ve held various roles in both primary and secondary settings, and managed youth services, so knew what the possibilities and restrictions were with each. While there are some similarities in settings, there are still quite major differences. For example:-

- Participation in school is compulsory; youth work is voluntary.

- Learning in the classroom is more formal and curriculum-based. I wanted our offer to at least feel more informal and experiential (the youth work way).

- Relationships in school are generally built on a hierarchical system. The spaces are heavily teacher-led for good reason. Youth work is more equal and negotiated, again for good reason.

- Their primary goals are fairly different. A schools main focus is on academic achievement. They have targets to reach. For us, it’s more about personal and social development, although we have targets for funding reporting.

- There’s a difference in learning models as well. Learning through curriculum versus learning through relationship.

There was almost a juxtaposition with how we wanted it to work and how it would normally be expected to work.

We wanted to deliver a programme that could blend both ends of the spectrum, where although a student may be expected to attend a session because they’re in school, there was permission for them to step out of elements they may not be comfortable with; where learning, while heavily structured, felt creatively freeing and almost as though it hadn’t been planned; where we could build trusting relationships around tough content swiftly and engage in a shared educational learning experience because this is their reality; where the focus was, yes, ticking a few curriculum boxes along the way because it helped schools, but helping the young people develop personally and socially, and especially from our angle, consider taking social action.

At the very least it was allowing them to realise they have an important voice in an ever silencing world.

Crucial was to have people with the relevant knowledge who could support us. This came in the form of asking questions to school staff I knew, linking to our own team who would be delivering, and regularly reviewing and adapting throughout in order to make it as accessible as possible.

Trauma-Informed By Design

From the earliest stages of planning, the programme was built to be trauma-informed by design. When working with content as sensitive as exploitation and violence, emotional safety isn’t an optional extra, it’s the foundation.

Every element of delivery, from the first email to the final reflection, is structured with care and awareness of potential triggers and emotional responses. Schools receive information in advance as to the various elements of the programme we may deliver, a DBS Letter of Assurance confirming our team are aware of their safeguarding obligations, and a content and accessibility statement, as well as risk assessments.

We are open, honest, and answer the questions posed, and it is important to accept that every single school is different and our approach may need to be adapted slightly each time to suit. In each instance, our delivery team is notified of these expectations. All of this not only better prepares our team but allows school staff to be better prepared practically and emotionally to support the students in their charge, as well as colleagues as conversations open up later on.

Holding those safe, accessible spaces is central to our work.

We regularly review delivery days, often the same day, and take on board feedback from schools. It’s a key part of our work, giving schools a chance to process what they’ve seen, heard, and felt in a supported environment. These reflective moments aren’t a courtesy; they’re an educational bridge, helping young people move from reaction to reflection, and from discomfort to understanding.

Our belief is simple: inclusion isn’t a bolt-on, it’s a baseline. Whether through accessible materials, diverse examples, or responsive facilitation, we aim to create learning environments where every young person can participate, engage, and thrive safely and with dignity.

Perfecting the Presentation

The presentation had key baseline markers:-

- It needed to be content rich in case we delivered in a school where follow-up workshops weren’t possible.

- It needed to be accessible, which meant including a variety of learning styles.

- It needed to be trauma-informed in order that we created a safe environment that allowed growth for all.

- It needed to feel like it belonged to Justice in Motion so had to include performative elements similar to those used in the show.

- It needed to fit into 50 minutes – the standard assembly time.

- It needed to be highly engaging, making you question, probe, reflect, and spark conversation long after you left the room.

Justice in Motion are passionate storytellers, and as a writer myself and someone who has given talks in the TED style, having an initial hook was important, but so was the structure and pacing. Whenever a ‘presentation’ or ‘extra assembly’ is mentioned in school, there is often a collective auditory groan because it can feel preachy and against the grain of the standard daily timetable. It’s uncomfortable, unknown, sometimes unwanted.

We had to cross that barrier.

Our hook was initially founded in the silence and unknown of a large, static, onstage visual. There was no explanation and absolutely no reference to it until the end of the presentation. If you want to capture attention surely there can be no better way than something ordinary set up in a slightly unusual way in a familiar setting. It provokes interest with the right amount of uncomfortableness for you to question why, and questions are good.

I wanted the presentation to quickly establish the idea that it was two-way. Students and staff were integral. If you’re delivering in school, you have been granted permission to enter ‘their house’. It’s no good being invited to someone’s house and taking over. We had to have the authority for delivery, paired with the understanding that this was a partnership.

That partnership was essential because this is the young people’s reality whether they’re individually far removed, on the fringes of being exploited, or already known to safeguarding and school policing teams. We know what we’ve researched, but they’re living it. People their age are being exploited and killed. We can’t shy away from facts, but the basic structure was that we started with interaction, fun, an element of moving, which eventually would lead to a contemplative, reflective state by the end. This structure has been seen to work through some of my other projects.

From the outset, the young people knew this was not simply a lecture piece.

Working with our Creative Director, we refined the presentation to include rap elements, statistics, visuals, audio, case studies, the law, and above all else, guidance and support. It was instantly clear that 20 minutes wasn’t enough, but if we ran with the idea that it was a presentation and not an ‘assembly’ in the traditional form, it didn’t need to sit neatly into the ‘assembly’ timing. What this has resulted in is schools being able to have their usual anchor point at the start of the day in registration time before transitioning into the programme, and this was important to us also.

Beginnings are crucial to the school day and provide tutors a snapshot moment to address any issues that may have occurred overnight, while also answering questions about the day and preparing students for what they may be about to witness, grounding them to the norm, especially key when it’s about to be a long day of change, information, and for many, enlightenment.

Entering the Classroom as a Freelancer

With the programme designed, we launched and subsequently delivered to thousands of students across the country. At the pilot, we went all out to test every aspect and were well supported by senior management and their safeguarding manager.

I cannot stress the importance of having a strong working relationship with the school from the outset and both parties understanding their responsibilities. It makes it so much easier in the long run.

The pilot was on home turf for me so it was possible to iron out logistics in person, but as we toured nationally, it hasn’t always been possible to do this. Rightly, it’s essential to have processes in place that ensure consistency and that as many questions as possible can be answered in advance, or where further questions emerge, there are answers available. Schools will always have questions, and rightly so.

At the pilot we delivered a presentation, then split into five completely different workshops, all delivered by either our practitioners or the school staff themselves, and rotated these across the day. We essentially had two spare bodies who could dip into different workshops to observe and by lunchtime our first piece of feedback had arrived from the Safeguarding Manager. One student who had struggled to attend lessons for nearly nine months had remained in workshops and produced work. Our approach was working.

Feedback is essential but it’s what you do with it that counts. Being a reflective practitioner in any deliverance, especially where education of children and young people is concerned, is key.

Where adults may be more reserved, our younger counterparts are not only good at voting with their feet, but are especially vocal too. The programme was constantly under review to the point that I would sit in each presentation progressing the slides and monitoring the engagement and impact of every single one alongside each word that our presenters would give.

Was the pacing right? Did the script need an edit? Were the images and graphics gimmicky and not ‘on point’? Were students looking confused at certain phrases? Why were they not engaging at the points we thought they would but were at others? Were we being as trauma-informed as we could?

Alongside ensuring the tech worked and that we ran to time, the constant monitoring not only fries your brain if you do four back to back presentations, but actually makes you appreciate how much difference there can be between two year groups, how much difference there is between a Period 1 group and a Period 2 group, and how the level of engagement changes between schools who are only half a mile apart. There were many pondering moments, probably the biggest being when we first delivered to Year 6 and Year 5. My heart was in my mouth whether the content was still relatable and appropriate there and whether we needed to provide a lighter touch, pare back, or ‘dumb it down’ as some might say. The feedback said it had landed perfectly. Our original launch at Key Stage 3 was landing in upper Key Stage 2.

The feedback we receive, much of it immediately after the day ends, has been essential in developing the work, notably the presentation which often gets the biggest response due to its effectiveness of engagement.

I would spend evenings in hotels between schools tweaking slide transitions by even half a second if I thought it would make a difference, and that level of questioning and perfectionism is important if you want a programme to land right. It’s not to say you can’t go off script. You have to expect to, and we did, often, but you should question constantly what the purpose is for you being there and what you are doing to ensure you’re still working towards that.

The entire programme was designed to engage, understand the young people’s level of expertise and experience, build and develop on that, while offering creative experiences they might not otherwise try, but which sparked enough interest for them to consider that positive option over the alternative. If you’re working in schools or any setting with young people, it’s important to remember that you are working WITH them. It’s a collaboration.

The feedback for our method has been phenomenal – in fact that word comes up a lot in testimonials.

What’s our secret sauce?

Well, it’s not really secret. I’ve alluded to it already. It’s having trauma-informed practitioners delivering a programme based on collaboration and engagement.

Being trauma-informed doesn’t mean avoiding difficult topics or questions either. It means asking them safely, with sensitivity to triggers, predictable routines, and the permission to opt out. Questioning, done well, is part of healing and empowerment.

The Day In Motion

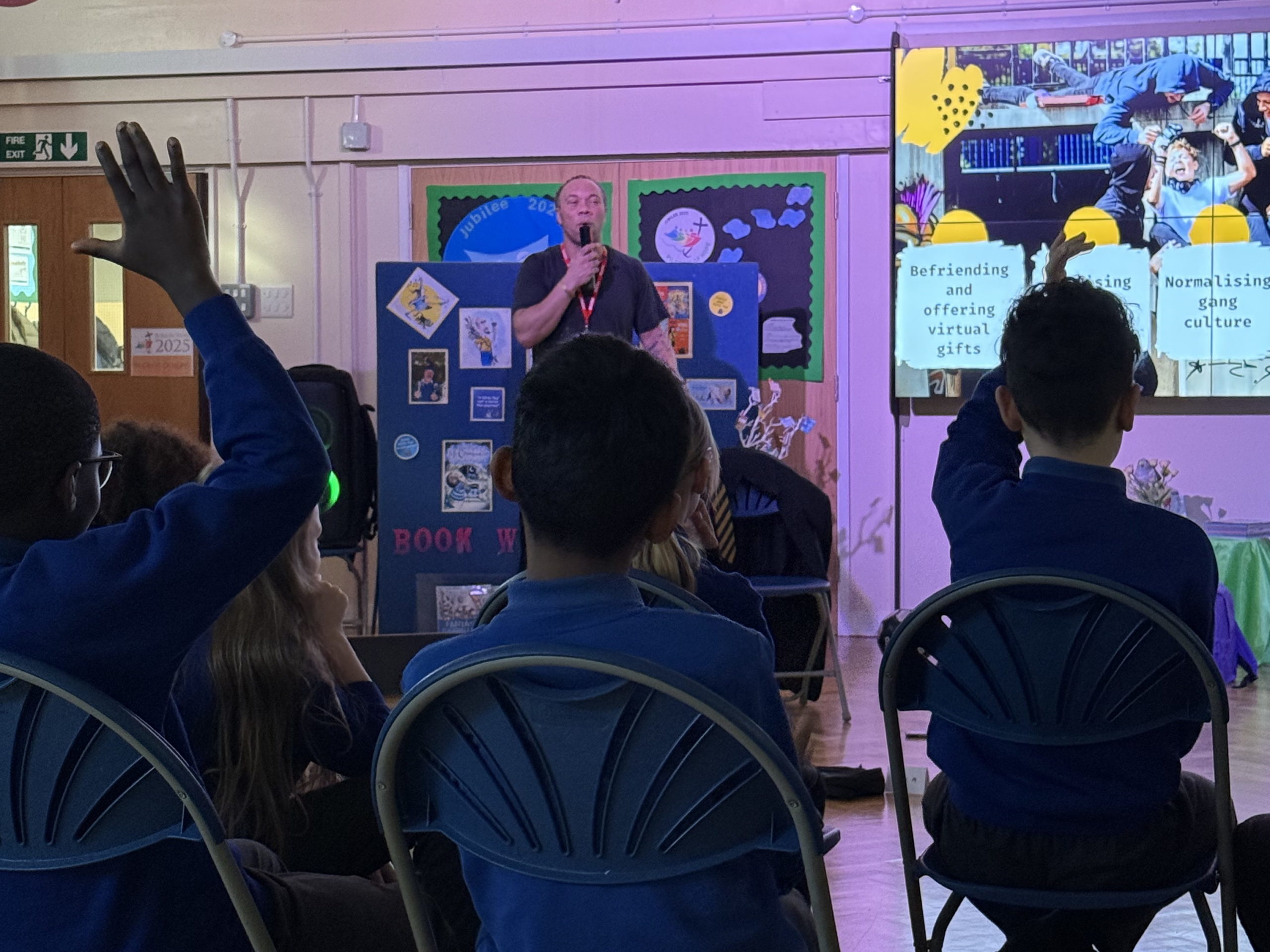

From the start of the day, we get students to join in with call and response in the presentation, asking questions throughout it, and stand up-sit down activities. Responses have sometimes been the same, and then there have been those that have surprised us and given our presenters cause to pause and reflect in the moment, as well as later on.

What we find is if one person answers, many more hands will feel the confidence from their peers and be compelled to follow suit, and we accept all answers. The young people don’t have to be right, but they do have to be heard. We’re not worried about whether they provide a correct answer or not, more that they provide AN answer and are allowed to use their voice.

The same is true for the workshops. We have a team that provides a creative, exploratory, educational programme allowing young people to step outside of the normal constraints of a class and its curriculum, and is fully built on the idea that we’re all do-ers together. This is not about us presuming we’re mini Einsteins and imparting our skills and knowledge, but sharing information, the process of which can only come from open and honest conversations, and you’ve guessed it, questioning. Us questioning them, but also them questioning us.

Each workshop is different and I could talk in depth about them, but let’s focus in on the one I deliver.

We begin again with the hook, and as a storyteller myself, my hook places me in a performative role. At this point, nobody really knows me, so this is a chance to test the waters and see how well they will engage. Without giving away the content, I ask for a volunteer to help me with a task. No context initially, just a volunteer. I guarantee a minimum of half the class will raise their arms in response to the question as did in a recent Year 8 workshop.

Then I build on what I need them to do, many hands remain, and the excited chatter begins. They don’t really know what they’re signing up to, but they want to stand up and be seen to be useful, helping out the new person in the room, especially when it’s tied to something presumably personal or local to them. All of this off the back of a question.

A reminder of the accessibility and trauma-informed approach here.

Those that didn’t raise their hand, I simply didn’t choose, but you could see they were still invested in the work from their body language. When I come out of the ‘performing’ mode two minutes later, we’ve usually reached very quickly a lightbulb moment for them on the dangers of county lines which is a great launchpad into the rest of the session, but they also have no idea whether I’m going to be ‘me’ or the performative version again. It keeps them on their toes and invested.

I’m not there to pick on an individual and make them feel uncomfortable so any volunteers are selected carefully, usually by sight as they come in the classroom. It’s often easy to spot those that might compared to those who likely definitely won’t.

On this point, I stand by the door as they come in and greet them unless I’m changing rooms rapidly and it’s not possible. This is crucial classroom and session management in my books. It sets a tone. I see you and you are welcome. Even when I managed one of the local youth clubs would be stood at the door at the start of each evening welcoming the group in and then remain a presence throughout. You have to hold the space and the classroom door has lots – What’s your name? What are we doing? Am I in this session? Why are the tables pushed back? Where do we stand?

And secretly underneath the questions above are the thoughts of who is the stranger and what are we about to be subjected to? Even non-vocalised questions exist.

So, I’m not there to pick on people and get them to engage. I’m there to give nudges and encouragement for it, for without questions, how else will they develop critical thinking, deeper understanding of the materials that are being offered, or develop their own thoughts on the content?

Throughout my workshop, I address questions to the whole class. At one point I stand in the middle of the circle and turn constantly so that I can see them all at different times, not only so that we all feel a bit closer, but so I’m not simply lecturing from the front. Does a circle activity in secondary school not hold the familiarity of circle time from primary where we are ‘one’?

Questioning is a key life skill.

It enhances communication, improves problem-solving abilities, and can boost confidence. Didn’t get something right? Well actually, by you questioning, answering, and reflecting, we’ve realised 10 others in the group feel the same…and we can do something about it.

I throw out to the room questions, follow-ups, and opportunities for discussion that are more than ‘just listen to my voice’ because heck, I’d be bored of myself after 10 minutes of talking if that’s how I ran it, and I’m in for a whole day, sometimes more!

By holding a space where young people feel they can be heard, we have developed a programme where questions do get asked by us as facilitators, and in return they ask us questions back. I’ve had many at the end of sessions want to stay on, ask more or discuss creative ventures they’re involved in. How much they’ll open up in 50 minutes if we allow them, but also tease out some of the extra thoughts that might be in their fascinating brains.

Questioning questioning

As any educator or person in a similar position will know, you can very quickly identify the ones that will step up and answer every question you pose versus the quieter ones who might struggle to answer even one, but does this really mean we should stop asking questions flat out as some reports suggest?

How do we do a register because calling out the name with an upward inflection is a question, is it not? Are they present or not? Somebody trips over and cuts their knee open. Don’t ask if they’re OK because again that’s a question, or even at the simplest level, dare I ask every child that crosses the threshold ‘How are you today?’ because I might just hear an answer that allows me to offer help.

Oh to have a connection that brings benefit to both parties!

I realise I might be taking it to the extreme with my examples, but where does it end? Where’s the line?

If I didn’t ask questions in any of my workshops, and this is true of the other practitioners, I wouldn’t have got a single volunteer and the powerful opener wouldn’t have worked. Instead we’d be on the boring lesson plane preparing to land in flat city on dull island.

If I then didn’t ask my follow up questions to the first activity, I couldn’t gauge within the first five minutes what their knowledge level is to help me pitch the content for the remaining 50 minutes. In one recent session, the floor had been opened from the beginning with the expectation of involvement and a co-collaboration that by the end I actually had to drop my last activity because questions were coming thick and fast, and they were more important than what I was going to get them to do.

They have voices, even the quiet ones. Let’s find a way to hear them!

The education pack that’s available to schools following our work was designed with questioning in mind. We don’t want all children to be silent copies of one another, their creativity squashed to zero, their confidence and voice on the carpet to be walked over.

This is why the pack contains solo activities, pair activities, group discussions, and even a debate. It’s an opportunity to not only learn in a variety of styles but for each individual to find the one that fits for them. The debating activity requires some role play but as the intro to the session says, ‘Not everyone has to play a role, but everyone should play a part’. What that looks like is different for each person but it could be that they step out of their usual comfort zone for the first time ever, especially if we ask ‘Fancy a go?’

I’ve been taken aback in some schools where they have struggled to engage with the open, fluid approach we take until we learn that ‘We normally teach by wrote. We put it on the board and they copy’.

That goes completely against the grain for us at Justice in Motion and me personally as a practitioner. I have to admit, having open dialogues and questioning the young people in my workshops often means I learn as much from them as they do from me, sometimes more.

I have lost count this year alone of the amount of staff who have told me that the workshop I have delivered has been one of the best they have experienced and a lot of that was down to the approach and the belief in the children. There are teachers who have noted the curriculum is too restrictive and not allowing creative space, yet one teacher almost felt that by me coming in they were given permission to once again throw the rule book out of the window and took my last group back to her classroom to ‘simply be creative and allow space to talk and ask questions of me, each other, and themselves’.

This applies to the coaching room too

Much of what we’re doing in schools delivering this education programme is coaching. It might not seem it, especially as I’ve mentioned education a lot, but coaching is ‘a collaborative process where clients are helped to unlock their potential’. I should know because away from Justice in Motion I’m a life coach, primarily working with children, young people, their parents, and educators.

Coaching is built on questioning. If I didn’t question clients, I wouldn’t be able to find out what they really want to achieve, what they’re willing to do to get to that point, or how they’re feeling at each step.

Apply this to Justice in Motion and if we don’t question, we don’t see what their creative abilities are, what effort they’ll put into it, how they’re currently feeling, or even what we or local organisations could do to help them on their creative journey – a journey that might prevent them being exploited into what they see as a glamorous life.

Questioning allows not only for collaboration but for signposting too.

If I didn’t question, I couldn’t coach.

That questioning and thinking through answers together allows a deeper level of self-reflection and actualisation, and it is this that has allowed those that I’ve worked with to have big small and big breakthroughs, be that stepping back into the school system after weeks stuck at home, attending residentials, dealing with friendship issues, through to building up their confidence and self-awareness of their emotional resilience, achievements, and abilities.

If we didn’t question and have two-way dialogue in the Justice in Motion education programme, there wouldn’t be the deeper levels of self-actualisation that we’ve seen, or the schools have seen after, there wouldn’t be breakthroughs like the young boys who could have succumbed to peer pressure but instead remained in a residency and performed in our production alongside the professionals, and we wouldn’t see the confidence levels soar like they do. We’ve had teachers tell us that a child who ‘performed’ at the end of an hour long workshop is normally ‘a mouse’ in the classroom.

Questioning, reflecting, understanding, collaborating.

A question can land how it needs to if handled correctly.

Back to my opener and I personally don’t believe the issue is questioning children as a blanket problem.

If we can’t question, how do we know they’re still actively engaged? How do we know they’re curious about the topic we’re discussing? How else are we reinforcing their individual talents and participation? How are we building them up to be reflective individuals, which is an important life skill?

- That egg wasn’t cooked all the way through? Got ill? What do we do differently next time?

- Didn’t have enough money in the shop? What do I need to do next time?

- Want to buy bed sheets for my first home and don’t know where to start? ‘Can I help you madam?’ – How on earth do I respond?

- I feel anxious about this situation. Oh. Well I’ve not learnt to question why that might be so it’s just me that’s the problem.

- I know I need to understand this county lines stuff, but I don’t know how to phrase my thoughts so I’ll stay silent and hope nobody asks.

- And so on…

I fully appreciate and accept there are children that will struggle to answer questions thrown at them. Even as an adult I can struggle with this, but then it is down to the facilitator of the space, be that a teacher, freelancer, coach, or otherwise, to get to know the people in the room.

We come back to the trusting relationship and questioning. Having an adult who cares enough to get to know them, no matter how briefly a period they are together, alongside how best to engage with them, who will word something in just the right way that may get them to answer, in whatever way possible.

And then we touch on accessibility. Answering a question how is possible. Yes or no will suffice sometimes, won’t it? Would a written answer be OK? How about thumbs or thumbs down? There are ways and means.

In coaching and in our workshops it can be difficult to build a relationship because you may be with the group for such a limited time, but as a teacher or school staff member, I would hope the time is spent (and I know it’s limited) to get to know your students well enough so that you can question each in the most appropriate way for them.

As somebody put on a related post online, ‘I trust teachers to know their classes’ – I support their sentiment.

I used to be terrified of the prospect of needing to know 210 students in my year group when I was a Deputy Head of Year. The reality was most didn’t come into my office or ever really meet me, but for the one occasion they might, it was up to me to work quickly with them to build that relationship in order that we could gauge together (even if this wasn’t verbalised) how far I could push the questioning with them. If I couldn’t ask ‘Is everything OK? Why are you here?’ I can’t help them and they can’t ask for the help they need. Stalemate.

Perhaps the issue isn’t about children feeling anxious about answering questions and us worrying about the fact they can’t or might struggle, and more about supporting them to understand how to manage any of these big feelings and emotions in order that they feel they can answer in the future, even if they do get the butterflies as they do it.

There’s a real art to questioning and being questioned of course. It’s a huge communication skill.

By cutting questioning in the class, are we setting up our children for greater failure in the future?

If they can’t ask or answer questions, how will they succeed in job interviews? What about working in what are often early careers in areas like retail and hospitality, where they need to speak to customers? What about if they wish to travel and need directions, but can’t hold that conversation?

Does this non-questioning stop at the classroom or will it expand to extra-curricular activities, after-school clubs, and voluntary organisations? I used to run Young Leaders and DofE training. If I still did this, would I not be able to ask questions that test their skill and knowledge level? Would I not be able to gently suggest ‘I hear your answer, but do you think there’s a better way?’

Soon we could make a whole generation of silent, insular children, terrified of questioning or being questioned. A generation of young people who have brilliant brains and ideas that could change the course of our world for the better, but fall silent because they’re too scared to deal with questions because nobody taught them the skills to regulate enough to do so.

And before anybody questions me, I appreciate neurodivergence, learning needs, and disabilities come into play, but I’ve also worked with children who fall into each of these categories who can be some of the most eloquent questioners and answerers known.

This topic opens a can of worms and provides more questions than it seems anyone is now allowed to ask. I’ve certainly done so in this post, but here’s my last…

Should we really stop questioning in the classroom?

Sorry, shouldn’t have asked that, should I? But if you’ve paid attention, I’ve asked a lot of questions throughout this article, and I bet it’s got you thinking, right?

Final reflection

Questioning isn’t just a teaching technique, it’s an act of trust. It says, I believe you have something worth saying, and it’s crucial to a classroom and a workshop space equally. Every time we ask or invite a question, we build a bridge between minds, experiences, and possibilities. When that bridge is strong, learning happens, confidence grows, and connection follows. As educators, facilitators, and coaches, our role isn’t to have all the answers but to hold the space where questions can safely live. Sometimes the asking is the learning and every time a young person finds the courage to ask or answer, that’s education, empowerment, and hope in motion.

About the Author

Roy Peach is Education Manager at Justice in Motion, and a professional life coach and youth worker specialising in creative wellbeing and EBSA coaching. Connect on LinkedIn @RoyPeach.